|

A CRITICAL CHRONICLE ON NOÊMIA GUERRA’S PAINTING

George S. Whittet - 1987 |

| |

|

I first met Noêmia Guerra in April 1965, at the Royal College in

London.

Noêmia, around her forties, showed herself to be an active woman,

judging from her firm attitude. What most impressed one

in her countenance were her eyes, which reflected a vivid

intelligence and immediate reaction, both mental and

emotional.

Noêmia and I talked about common Brazilian friends. She also told

me she had been living in Paris, in a rented studio in

Montparnasse, since 1958.

Noêmia added that she was about to exhibit her work, in the

coming month of May, at a small gallery in London’s West

End.

|

|

|

|

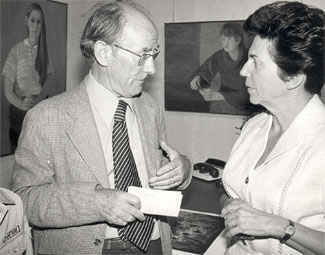

George Whittet and Noêmia Guerra |

|

|

| |

|

As I went to Paris quite frequently at the time, in order to

visit galleries, I proposed, if she was interested, that

she should take me to see her paintings that would be

exhibited in London, or at least some of her other

paintings. |

|

|

|

The opportunity arose and I was then able to see the artist’s

work in her Paris studio, and later her first exhibition

in London, in the tiny St. Martin’s Gallery, directed by a

Venetian émigré called Victor Zamattio. That exhibition

had been organized by Mrs. Raquel Braune, the Cultural

Attaché to the Brazilian Embassy, who also organized a

welcome vernissage, bringing together art critics

and personalities of London society.

In a critique on the exhibition, I wrote: “Noêmia Guerra’s oil

paintings show great vitality and spontaneity in their

composition, where the “cobalt blues and violets” suggest

the sky, through abstract references (this sky I would

soon see for myself in Brazil). The compositions, almost

abstract, suggest shapes in space by means of color and

shade modulations.

In fact, the essence of her compositions was “the movement”

produced by the variations of “shapes-tones”, suggesting

“dancing figures” to the spirit of the beholder...

It was impossible to find, in the animation of such nature, any

trace of influence of the short course given by Professor

André Lhote, which she took in 1951, when the French

professor had been invited to give a course in Pictorial

Composition at the Municipal Institute of Beaux Arts in

Rio de Janeiro, where Noêmia was studying.

|

|

|

|

The hard, well-defined contours that Lhote had borrowed from

Cézanne, and later from the cubist movement, were of no

interest to Noêmia. Color, in all its potentiality, was

the predominant factor in Noêmia’s paintings; gradually

these color modulations introduced, in her pictorial

creation, more associations in the beholder’s

understanding and spirit.

I liked Noêmia Guerra’s paintings so much that I introduced her

to Mr. Alwin Davis, a young designer who had worked in

Hollywood and had returned to London in order to start a

gallery in Mayfair. Mr. Alwin Davis and his partner, Mr.

Ronald Dongworth, agreed to include Noêmia Guerra’s

paintings in an Exhibition at the Alwin Gallery in the

following year.

1966 was an important year in Noêmia Guerra’s career. Firstly,

there was a big individual exhibition at the Jacques

Massol gallery, on the rive droite, as well as

Noêmia’s participation in the “Three Artists” exhibition

at the Alwin Gallery in London, for which I wrote a

preface. Jacques Massol invited me to write the

introduction to the catalogue for the Paris exhibition.

Below, there is an extract from that introduction. |

|

|

|

After meeting Noêmia Guerra, I visited Brazil. In the first

place, to see and comment on the São Paulo Biennial, which

allowed me to improve my knowledge, not only of Brazilian

art, but also of the social and cultural aspects of

Noêmia’s country. In particular, the landscapes, the

people, the almost surreal contrasts between wealth and

poverty, the Afro-European ethnical mixtures, the “silent”

– though always present – descendants of the Indian

tribes, an indispensable element of the racial mixture of

the Brazilian people.

This experience allowed me to better appreciate the reflections

of Noêmia’s past, already evident in her paintings.

With these impressions fresh in my retina, and the outline of the

peaks of the range called Serra dos Órgãos emerging

from the red soil, the plane was preparing to land at the

Galeão Airport in Rio de Janeiro.

I realized then that this “Tropical Brazil” was spiritually and

chromatically expressed in the tropical images of Noêmia’s

landscapes, as we can see, for example, in her penetrating

painting “Tijuca”, the urban forest situated in the

mountainous region of Rio de Janeiro. |

|

|

|

Tijuca - 1966

Oil on canvas - 81 x 65cm |

|

|

|

|

|

In Rio, a friend accompanied me in a car and took me to visit

several characteristic places, including the Tijuca

Forest. During the outing, while I felt immersed in the

green atmosphere of the tropical forest, Noêmia’s painting

“Tijuca” came to my mind, with the colors of the forest;

it was precisely this! A dark green environment forming

the backdrop, reddish ochre contrasts of the soil, the

rhythm of the ups and downs of the hillside, suggested in

the painting by means of light green modulations, like

sunbeams shining through leaves and branches. Suddenly a

silvery shine appears amidst the somber rocks; it was a

waterfall reflecting the blue of the sky.

Once more, I felt perception as an original, creative act, thanks

to which we are simultaneously inserted in an environment

and transported to some recollection.

I went so far as no longer to consider that the merit of a

culture rests on a technical skill, but on a rumination of

a popular taste connected with the modernism of the

twentieth century. Above all, we should consider a

painting as a graphologist would, and read in the

composition the painter’s character. Art, more than ever,

is the signature of a personality.

To submit to electronic calculators and to optical abstraction is

to renounce the artist’s spiritual power. Fortunately,

there are still artists who are faithful to the rhythm of

their own magnetism. Noêmia Guerra is one of them. Her

painting radiates a luminosity that is “Painting”, this

precious substance that has recently suffered so much

devastation and constrained inventions.

As a poet, I believe that, in her landscapes and dances, Noêmia

Guerra embraces life with courageous joy, to which few

surrender themselves. As a critic, I am sure that her

message is intelligible, with no need to be decoded. It is

Painting in its pure state, with universal meaning. Less

than three months after her exhibition in Paris, Noêmia

showed eighteen paintings at the Alwin Gallery in London,

a total of forty pictures in the two exhibitions.

Durenmatt said, quite rightly, that “the artist cannot accept a

law, unless he himself has discovered it”. |

|

|

|

Progressively Noêmia discovered, in her paintings that are so

personal and euphoric, that there is no pre-conceived form

in which a mental image may boast of its materialization.

Each composition is a step taken by the artist in his

journey through a landscape of light.

Later, in 1966, I was invited to take part in a jury of European

critics at an international exhibition organized by a

small municipality in Slovenia, Sloveny-Gradec, in order

to award the prizes. I was happy to see that Noêmia

Guerra’s luminous painting – “The Cliffs of Algarve” – was

far ahead of the other Yugoslav and European paintings.

.

|

|

|

|

|

In 1967, Noêmia and her partner, Julian Luna de Prada, spent part

of the Winter in Lebanon, where they met the people in the

suks and discovered the ancient dignity in the

isolated ruins of Baalbek, which introduced new themes to

Noêmia’s compositions.

Julian and Noêmia had fun watching the arguments in the suk

marketplace: the clothing, shawls, embroidered

scarves, like flags shining under the sun rising in the

gaps between the narrow alleys.

During her trip to Lebanon, Noêmia produced numerous drawings and

watercolors for later work based on such “studies” after

returning to Paris. The trip to Lebanon and the annual

stay at Lagos, Algarve, gave Noêmia motifs for the

composition of her paintings that would be exhibited at

the Alwin Gallery in early 1968.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rocky Hillsides in Algarve - 1969

Oil on canvas - 120 x 154 cm |

|

Noêmia Guerra’s paintings may have different themes, but we

always see a unified approach and treatment. For Noêmia

Guerra, to paint movement is not to describe it by means

of shapes, but to create a composition that will give the

sensation of movement based on a modulation of tones.

Thus, in her compositions in which dancers, with grace and

vitality, are blended into the background of the painting,

a modulation of tones is established making a counterpoint

with other dancing image-shapes in the foreground, marking

the rhythm, by means of these “value-color” contrasts, by

the artist’s decision.

In the paintings “Rocky Hillsides" and "Algarve Coastline”, the

contrast of the “value-colors” creates a new luminosity,

with its own light rays. The artist’s alienation in

society is a contemporary cultural discomfort; but for

Noêmia, there is no alienation between the variety of the

spectacle offered by life and the warm, empathetic

response she enthusiastically transmits to the beholder.

|

|

|

|

|

During the year 1969, Noêmia had a new Exhibition at the Jacques

Massol Gallery in Paris, and at the Alwin Gallery in

London; the two exhibitions were simultaneous. They were

both noteworthy for the diversity of themes inspired by

direct personal contacts made during her trips. In my

introduction to the Alwin Gallery exhibition, I

stressed the development and maturity of an innate talent,

nurtured by experience and continuous efforts.

In the paintings inspired by the watercolors made on the spot

when she visited Brazil, Portugal and Lebanon, the human

figure is placed naturally in the landscape. I wrote in

“Le Monde” (2), “Noêmia Guerra went back to Bahia

(Brazil) in 1968. Salvador, the capital of this state, has

splendid 17th and 18th- century

baroque architecture, but Noêmia’s imagination received

greater stimulus from the people that give life to the

sun-stricken environment; the Salvador “Fish Market” is a

singular work, as it is a work of art painted with

extraordinary audacity in terms of colors and movement.

Each of the five panels is a complete painting, which may

be admired as such separately, but which even so is part

of a pictorial composition. In my view, “the hues” arouse

an exaltation, when they create a space and bring forth

“the unexpected”.

In 1973, Noêmia presented her fourth individual exhibition at the

Alwin Gallery. I wrote about her in “Pictures on

Exhibit” (New York) (3): “The Cliffs of Algarve

offer themes to Noêmia Guerra. The variations of the

motifs, which are constantly beaten by wind and waves,

reveal, thanks to a vibrant painting, a growing strength

in the composition and in the perception of tone

modulations when they depict the shapes of cliffs under

the sun”.

Four years elapsed between Noêmia’s fourth exhibition at the

Alwin Gallery and the next, at a gallery also organized by

her friend Raquel Braune.

After a very successful vernissage at the Stephen Maltz

Gallery (22 Cork St., London) in 1977, I wrote: “I found

Noêmia Guerra’s paintings even stronger and more dynamic

in the imagery and energy employed. Her main

characteristic is exuberance, with a command of one of the

most elementary expressions of the life force of any

society: dance. Noêmia’s favorite dance is that of Brazil,

her country of birth: the samba. She paints men and

women dancers, expressing their sensuality, in such a way

that the tactile quality of her painting involves the

texture and the orientation of her strokes. In some

compositions, the brush seems to follow the forms and to

caress the pigments, in a choreography that is patently

sexual. The dominant tone is red, the red of roses, of

sunsets, of ripe fruit, of wine, of blood, symbols of our

present world of violence, but kept under control by the

expression of a common joy, synthesized by the samba

music, which is a reflection of the soul of the Brazilian

people”.

In 1979, Noêmia exhibited, at the Marcel Dernhim gallery in

Paris, her most recent paintings, which demonstrated a

fantastic contrast between stability and movement. In my

critique (4) I wrote: “thanks to a constant

development towards a more expressive relation of shapes,

her “iridescent painting” projects a luminosity from

within, of a rare personal characteristic; whether the

brilliant facets are reflected in static or dynamic form,

as if animated by a breeze, a subtle modulation of light

makes all the elements of the composition move as if by

refraction”.

In the year 1981 she had another exhibition at the Marcel Dernhim

gallery. In the portraits, Noêmia Guerra took an important

step forward in relation to the previous two years,

achieving a remarkable simplicity. Knowing some of her

models in person, and the affinity between them and the

artist, I admired the honesty with which she showed them

“in two dimensions”, in a generous, audacious and

uncommitted summary.

She took part in the Brazil Festival, which was held at the

Barbican Centre in London, with three works. In my

introduction to the catalogue of this exhibition, I wrote:

“Noêmia Guerra is among the best women artists of Brazil”.

Two expressive compositions, in stunning colors, translate

a warm involvement with the life of the people, be it in

lively scenes on the beaches of Algarve or in groups of

dancers in Bahia”.

In the most recent years, Noêmia has spent the Spring and Summer

in her atelier at Lagos, Algarve, and Autumn and Winter in

her atelier in Paris.

Noêmia has become well known painting portraits, which she

considers increasingly stimulating. I shall comment on

three of the most impressive, which I was able to see in

1986, when I went to Paris in order to pose for a portrait

in Noêmia’s atelier.

The first portrait that attracted my attention was that of a

bearded young man, wearing a blue t-shirt with a drawing

in white lines on it, representing a boy that was jumping.

To my question “why this drawing?” Noêmia answered: “the

drawing is by Portinari, a picture of his son, the Maths

teacher João Portinari, who was wearing this t-shirt when

he came to visit me during one of his trips to Paris. This

drawing has become the logo of the “Portinari Project”

Institution, founded by his son João in order to preserve

the work of Cândido Portinari, an exponent of figurative

painting in Brazil, after his death in 1961.

I took delight in the expression of tenacity of the bearded man

and the subtlety of the painter Noêmia Guerra, who, though

copying Portinari’s drawing printed on the shirt, made it

one of her own creations.

The second portrait impressed me because I recognized in it the

model Maria Nunes, now a young mother, posing with her

son, an eight-month old baby called Igor. The baby’s pose

is the strangest I have ever seen in a Madonna painting –

the baby was naked and standing on his mother’s knees; I

admired the composition and the chromatic quality, in

perfect harmony with the youthfulness of the models.

The third portrait, equally noteworthy, was that of a famous

Brazilian opera singer who lives in Paris, Maria

d’Apparecida, wearing her characteristic hat. In the

background of the composition, but incorporated into its

structure, was an imaginary scene, the figure of Feliz

Labisse, discreetly modeled, himself painting a portrait

of Maria d’Apparecida. This “pictorial evocation”, as

there had been past links between the people portrayed,

reveals the imaginative way in which Noêmia treats her

composition, which is rare in modern portraits.

For Noêmia Guerra, each composition is a challenge and a stimulus

to represent her mental images, and not just a technique.

To call her an expressionist would be an inadequate cliché to

describe Noêmia Guerra’s style; in all her paintings, such

as those I have seen, one after the other, in the course

of twenty-three years, there is rather a marked

“subjectivism”, revealing her maturity in approaching the

themes, reflecting her inward personality, composed of a

generous spirit, fighting difficulties, appreciating the

forces of Nature, using all color resources, through a

personal experience and acute sensitivity.

George S. Whittet - 1987

References:

(1)

Studio International, May 1965.

(2)

Le Monde, October 30, 1969.

(3)

Pictures on Exhibit - New York, February 1973.

(4)

Art and Artists, February 1973. |

|